What Do We Feel When We Connect?

Meaningful interactions can evoke a range of emotions, yet there are some overarching patterns.

Moments of human connection tend to be very positive experiences in everyday life, benefitting our immediate mood and contributing to the quality of our relationships.

Yet despite their positive impact, when I interview and survey people about moments of human connection, their experiences are not necessarily joyful, though they sometimes are; they also aren’t necessarily brimming with the fear and courage that comes from sharing our most vulnerable selves, though that’s certainly a meaningful way to connect with the people we want to feel close to in our lives.

There are many things we do to connect with others, including supporting each other emotionally or with practical needs, having heart-to-heart conversations, expressing affection, or even just having a good laugh—and any of these experiences will have their own, often complex emotional tone.

The Many Feelings of Human Connection

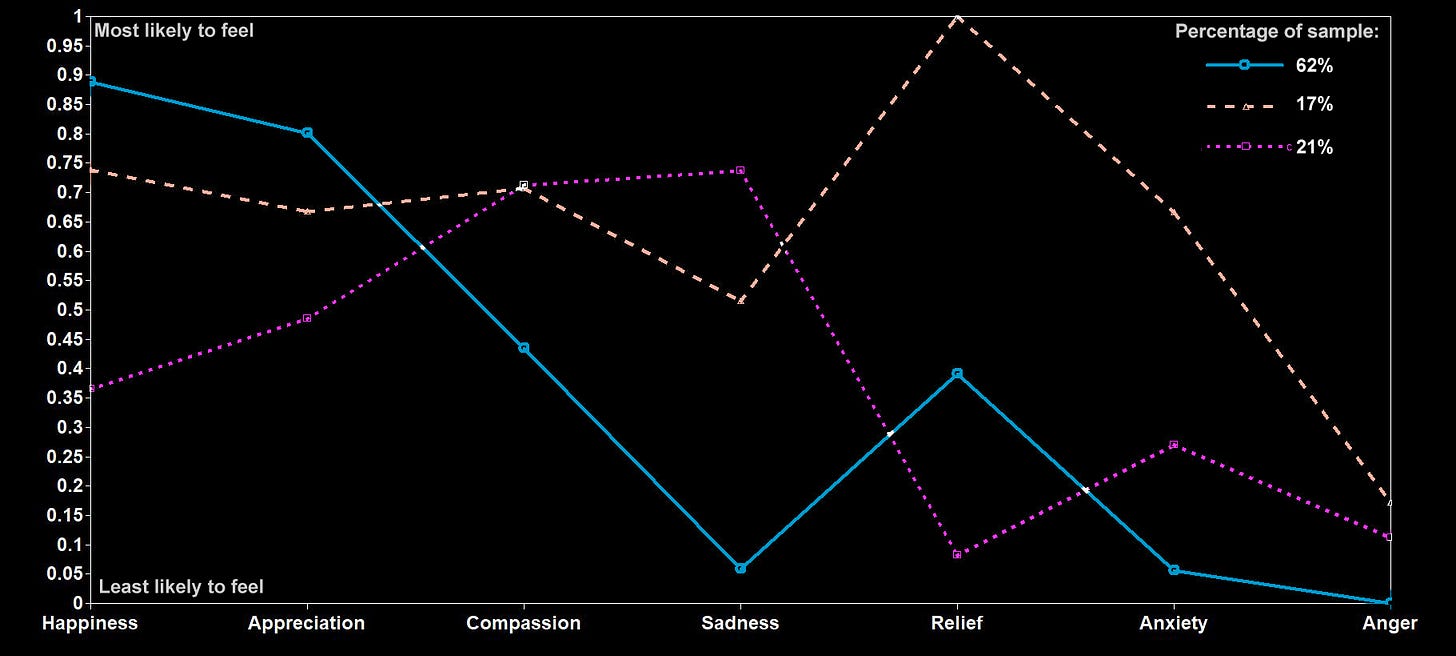

As an example of the different ways feelings can be experienced in meaningful interactions, the below graph shows the emotions that a sample of 341 people1 reported feeling (from a checklist of emotions) when I surveyed them about meaningful moments of connection they had recently experienced with people in their lives.

I used a statistical model (latent class analysis) to sort people into different groups based on what they felt in their moments of connection—the model shows how likely people in each of these groups were to report having felt each feeling listed.

The model grouped people's experiences of meaningful connection into three different types:

62% of people (the solid line) did seem to have a happy experience that they appreciated, and felt few negative emotions like sadness or anxiety. Some of these experiences likely included what researchers call positivity resonance, where we feed off of one another’s positive emotions in an upward spiral of joy.

17% of people (the dashed line) had what I would call a vulnerable moment of connection, where they felt sadness, anxiety, or even anger, but these more challenging feelings were balanced by relief, happiness, and compassion. Often I see these more positive feelings following the more vulnerable ones as we regulate our emotions through the process of connecting.

21% of people (the dotted line) felt mostly compassion for another person, and sadness—this kind of experience often occurs when we support another person emotionally, a very meaningful way to connect, but not always a joyful one.

Now, this model would have looked different if I asked it to organize participants into more groups, or if I included more or less emotions. But this example showcases how people generally have complex emotional experiences when they connect, often feeling more than one identifiable emotion, sometimes both positive and negative emotions in one episode.

Feeling Uplifted and Appreciative

I’ve found that the overarching emotional experience people describe in moments of human connection is uplift—a weight off the shoulders, an elevation of spirit. Even if we enter the interaction feeling anxious, we may feel comforted over the course of the moment of connection. In painful moments, like connecting with a loved one who is passing away, we may feel a deep gratitude arise and mix with our apprehension and grief, lifting us even in our pain.

Even anger appears in meaningful connections—it’s more often anger directed at someone or something other than the person we are connecting with, though engaging with one another during conflict to find our way to connection is a vital kind of meaningful interaction.

Our gratitude, or appreciation, is a useful signal that we’ve had a meaningful interaction. Even if all we did was wave with a passerby on the street, we feel appreciation that our mind just encountered another mind in a satisfying way. Indeed, people in all three groups in the graph above were fairly likely to have said they felt appreciative regardless of the kind of interaction they had.

Engaging Meaningfully Around Any Emotion

The key to connecting meaningfully in everyday life isn’t having an interaction that feels happy or even comfortable in the moment (though human connection can be joyful and comfy), nor is it required that we face vulnerable emotions alongside everyone we want to feel connected with. Meaningful connections happen when we meet one another where we both are at emotionally in that moment, within that particular context.

So, when we think about what kinds of experiences feel meaningful, we can actually seek to engage with others in ways that elicit a whole spectrum of emotions. What matters is responding wisely to the needs of the moment—is it a time to laugh? Is it a time to comfort one another? Is it time to have a heart-to-heart? Is it time to feel solidarity in our righteous anger? Is it time to find one another again after a conflict? Sometimes things get a bit messy before we find our flow together, and that's OK.

Regardless of the kind of situation we are in, if we enter an interaction with openness and curiosity, and try to show one another that we understand, validate, and care about the feelings that we each express, we are on the right track to meaningful human connection.

A version of this article also appeared on my Psychology Today blog.

All participants reported being United States residents. Participant age ranged from 18 to 76, with mean age being 38 with a standard deviation of 17, and median age being 34. Participant gender identity was reported as 54% women, 45% men, less than 1% non-binary, and less than 1% preferring not to say. The racial/ethnic background of participants was as follows (participants could check multiple categories): 2% American Indian or Native American, 11% Asian American or Pacific Islander, 13% Black or African American, 21% Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin, 61% White, and 2% selecting Other. The highest level of education completed was reported as: 1% less than high school, 36% high school degree, 11% 2-year degree, 31% 4-year degree (e.g., B.A., B.S.), 18% master’s degree, 3% PhD or professional degree (e.g., J.D, M.D.). Annual household income was: 5% less than $10,000; 8% $10,000-19,999; 9% $20,000-29,999; 7% $30,000-39,999; 7% $40,000-49,999; 8% $50,000-59,000; 8% $60,000-69,999; 7% $70,000-79,999; 3% $80,000-89,999; 8% $90,000 -99,999; 15% $100,000-149,999; 10%, $150,000 or more; and 5% preferred not to say. The median household income was in the range $60,000-69,000. Region of residence was 56% suburban, 33% urban, and 11% rural.